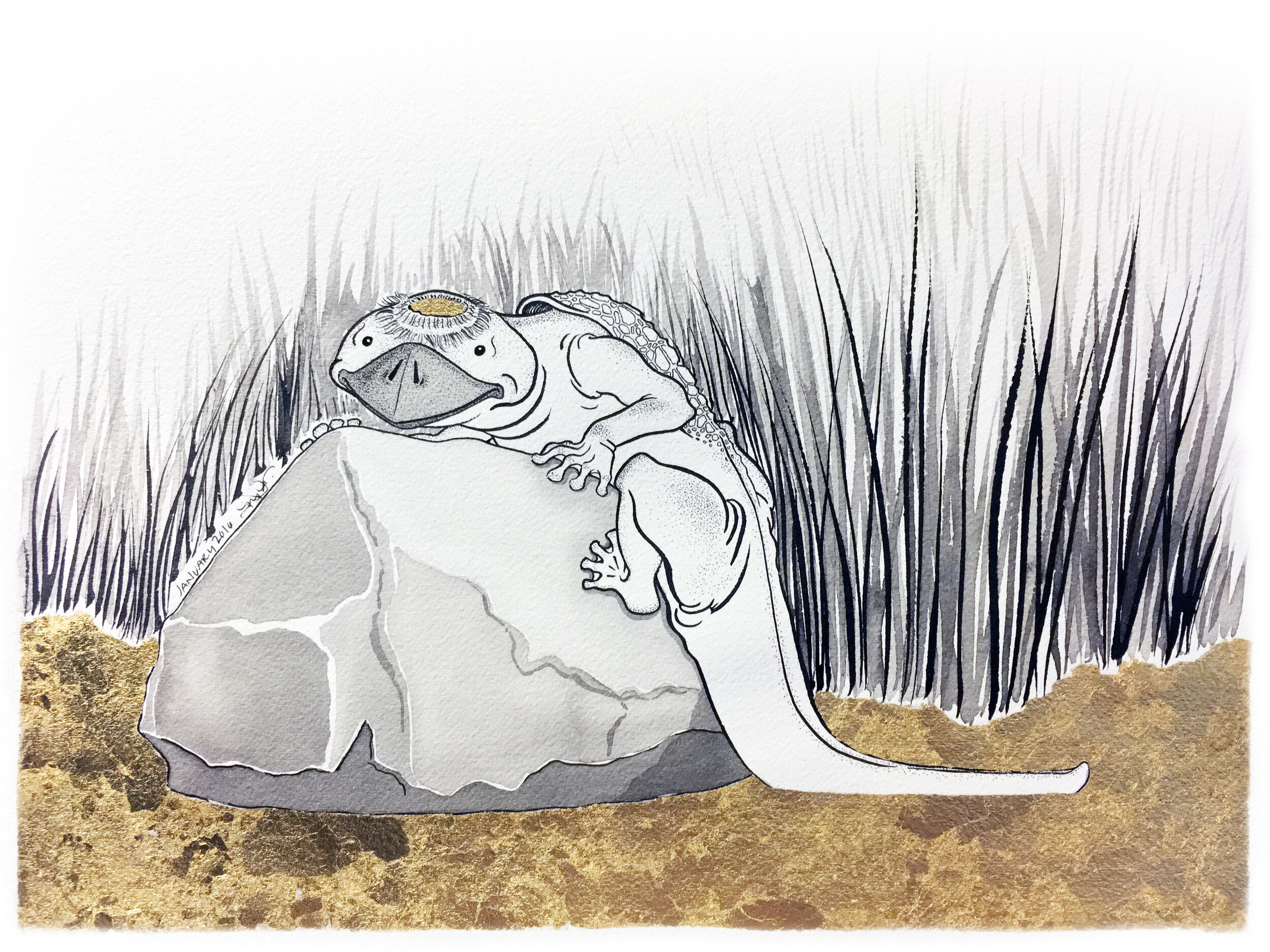

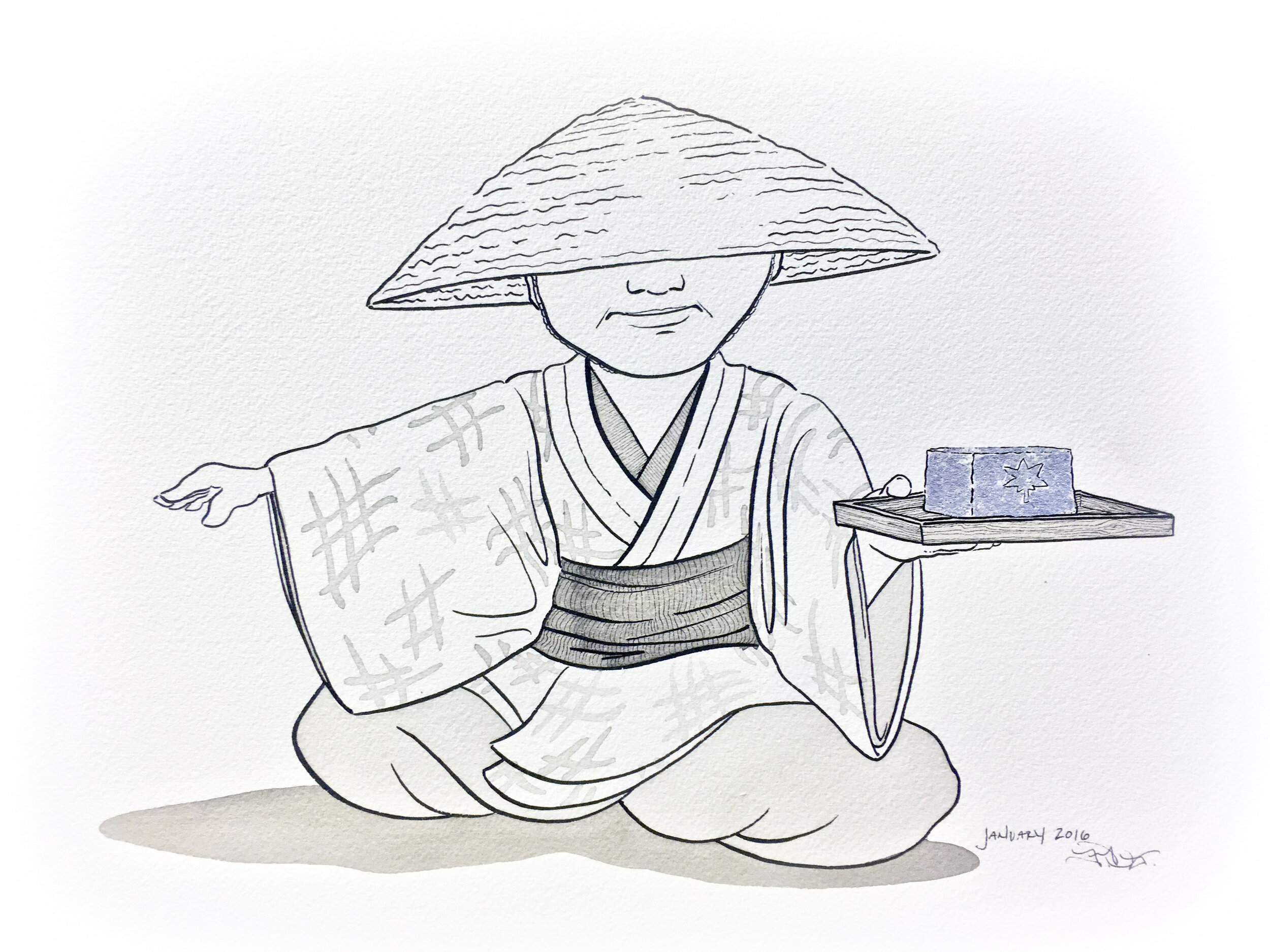

Year of Yōkai

What is a Yōkai?

Yokai, in Western culture, are best understood as monsters. But that title doesn’t really get to the heart of what they really are. They are monsters, yes, but they’re also spirits, guardians, temptations, rationalizations of unexplainable occurrences. They’re inanimate objects that have gained sentience. They’re real animals and animal behaviors personified and exaggerated. They are people that have become animal-like, and animals that have become people-like. They are an insight into Japanese history and thought. They are lessons, folktales, and superstition all wrapped into one.

Year of Yōkai - Some still available

12 individual illustrations

Medium: Ink, gold copper and silver leaf on cold pressed paper.

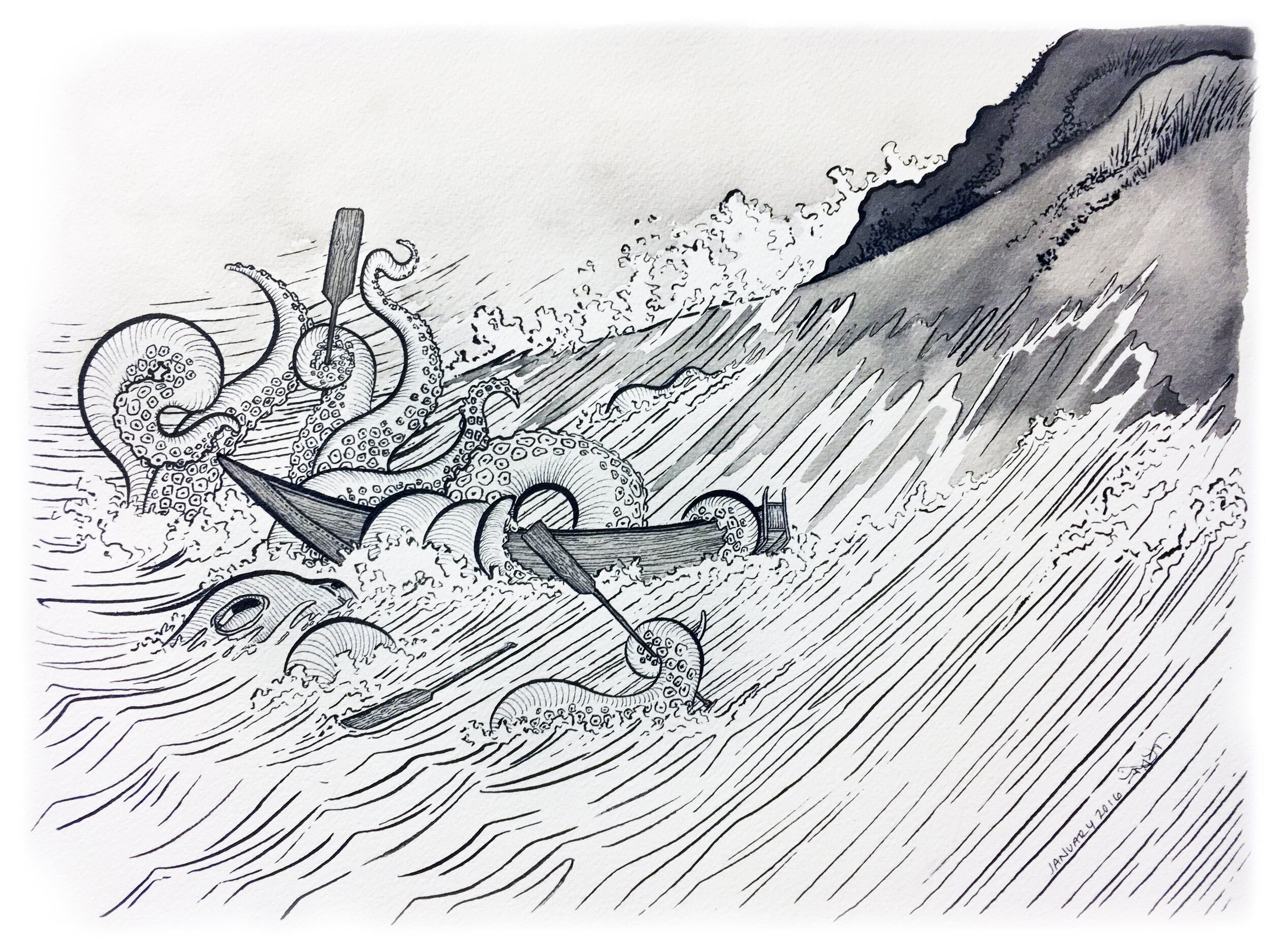

If I could make yōkai real, I would. But then I think about how over the ages yōkai have been born out of rationalizing the unexplainable or giving sentience to a thing that was just personified.

Some they’re the bearers sadness, fear, and frustration.

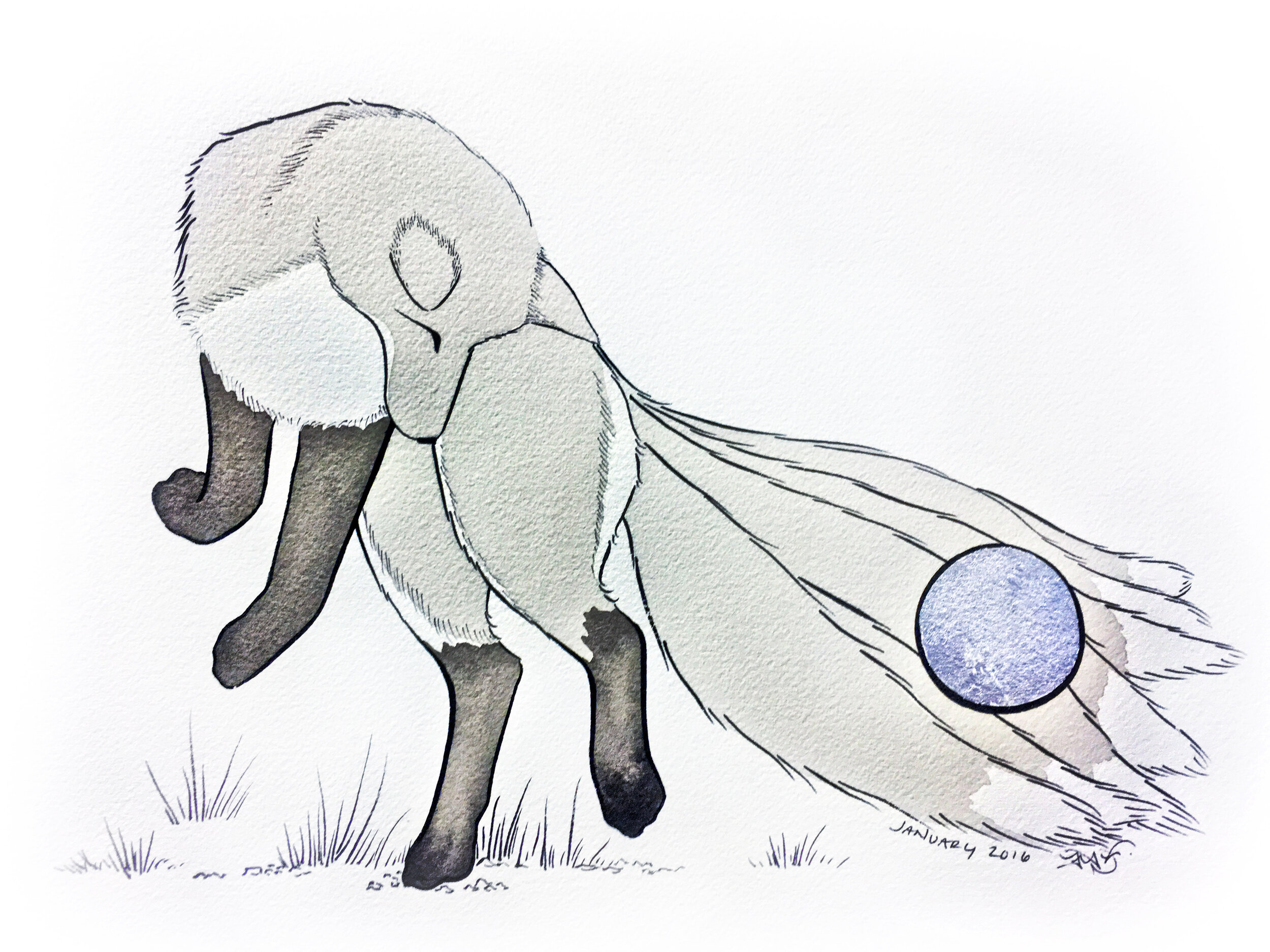

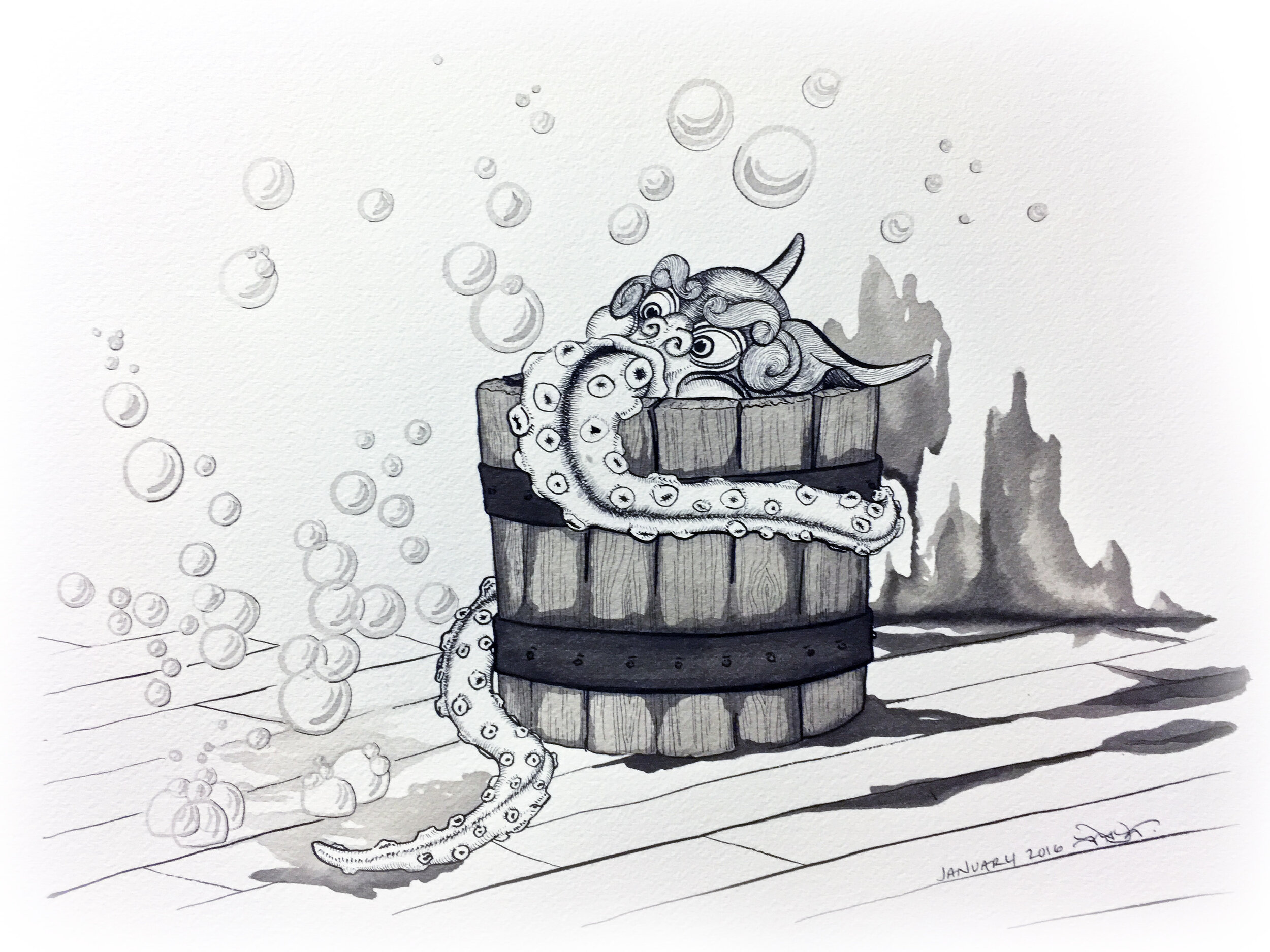

Other times they bring happiness or excitement.My husband used to play Pokémon GO when he would take our on walks. I remember jokingly asked him, “Why play when you have your real Pokémon right at your side?” Our dog is like a Pokémon; a monster that wants to go with us everywhere. We had to train and feed her. She has goofy habits and makes weird noises.

Pokémon are this generation’s yōkai: Ninetails is a Kitsune yōkai. Magikarp evolving into a Gyrados is the famous story of the Koi’s perseverance and transformation into a great dragon.

Our dog is our real life Pokémon, and Pokémon are really just yōkai. Perhaps our callousness to the world has just re-identified them as ordinary animals. Perhaps our clinical definitions of extreme emotions don’t accurately express how depression or mania can feel like it is its own beast. When I mull this over, I can’t help but come to the conclusion that yōkai might actually be real.

—T.G.Novy